Introduction

Uganda is a country blessed with abundant rainfall.

For many years, digging a borehole meant access to water.

With support from developed countries, boreholes have been constructed nationwide, and hand pumps have been installed across rural communities. These efforts have supported the lives of countless people.

However, today the situation is changing.

In some areas, pathogens have begun contaminating groundwater. In others, salinity has increased to the point that the water is no longer suitable for drinking. Water that was once taken for granted is quietly—but steadily—being lost.

The consequences are serious. An increase in diarrheal diseases believed to be linked to drinking water has been reported in various regions.

We learned about this situation through our local business partner in Uganda. The reality is that even where boreholes exist, safe water is no longer guaranteed.

Based on this information, we explored whether Japan’s hollow fiber membrane technology combined with an off-grid purification system could contribute to solving this challenge. To verify its feasibility, we launched a pilot project on the ground.

Site Selection

The site assessment was led primarily by our Ugandan partner. They visited multiple communities, carefully reviewing groundwater conditions, existing facilities, and listening to residents’ voices.

The number of potential sites exceeded our expectations. In every village, people expressed a strong desire: “Please bring this system here.”

However, we could not install the system everywhere.

After multiple discussions with our partner—considering both urgency and long-term sustainability—we selected Kasambya Village in Nakasongola District as our pilot site.

Although several boreholes exist in the village, the groundwater has become saline and is no longer suitable for drinking. As a result, residents rely directly on water from Lake Kyoga.

Lake Kyoga water has high turbidity, and cases of diarrheal illness linked to water are reported in the area.

In surrounding communities, groundwater salinization is spreading. Some villages collect rainwater; others transport water from less affected areas. Among them, Kasambya’s situation was particularly severe. With a population of approximately 550–600 people, it was also suitable for a pilot-scale implementation.

This is why we chose Kasambya as the first step.

The Children’s Reactions

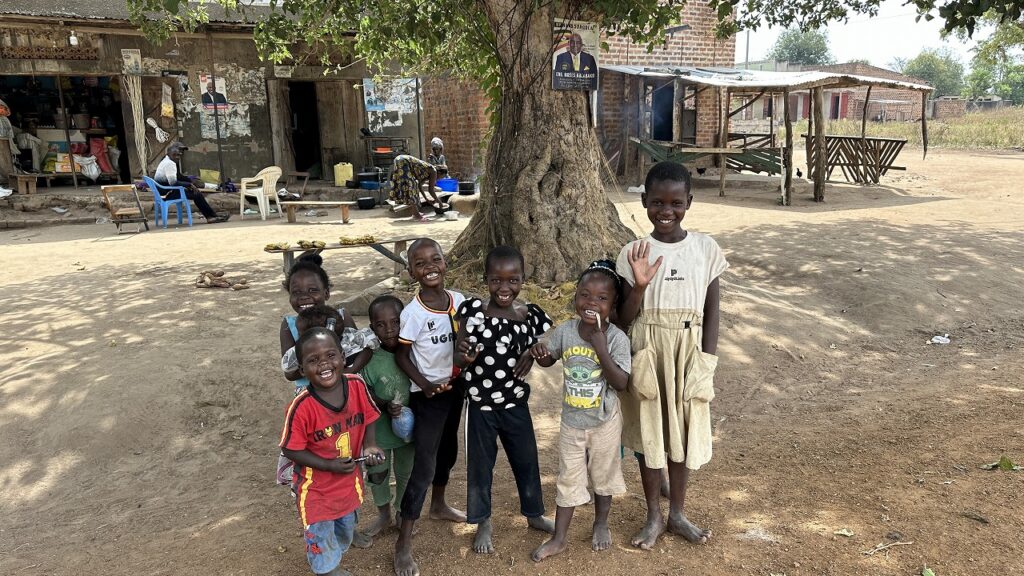

What left the strongest impression when we entered the village was the expression on the children’s faces.

We had been told that residents were cautious about outside investors and land-related developments. We expected some distance at first.

But the atmosphere was completely different.

Later we learned that our previous project in a neighboring village had created a positive reputation that had already reached Kasambya. When we pointed a camera at the children, they responded with slightly shy—but radiant—smiles.

That told us everything.

An Unexpected Challenge

Just before installation, we discovered that the building we had planned to use was suddenly unavailable.

For a moment, we were stunned.

But there was no time to stand still.

“Let’s build one.”

In Uganda, simple structures made of brick and cement can be constructed quickly. While bricks were laid and cement was mixed, we moved simultaneously—preparing solar panels, installing tanks, assembling purification units.

Everything happened in parallel.

There was no margin for error.

The only reason this intense coordination was possible was because our business partner had undergone long-term technical training in Japan. They understood the machinery, the electrical flow, and the water system.

Instead of asking, “What should we do next?”

They said, “I’ll handle this next.”

In the field, that difference is decisive.

Technology does not reside only inside machines. It resides in people.

The Reality of Lake Water

The raw water source is Lake Kyoga.

When pumped into the tank, the turbidity is immediately visible. It is far from clear.

We assumed residents might use chemical treatment or basic filtration, as we had seen in Senegal where communities used coagulants to settle sediments.

But in reality, the only treatment was boiling—using firewood.

There is no turbidity removal process.

Collecting firewood, starting a fire, and boiling water daily is a heavy burden. Moreover, boiling does not address salinity or remove all physical contaminants.

In recent years, water-related diarrheal diseases have sharply increased in various parts of Uganda. As groundwater contamination and salinization progress, dependence on traditional boreholes is becoming less reliable.

The Power of Safe Water

Even while construction was ongoing, children began lining up with jerrycans.

Although official distribution had not yet begun, they waited patiently.

When purified water finally flowed from the tap—clear and visibly different—the children drank it without hesitation.

Safe water changes the atmosphere of a place.

That morning, as we saw a line forming in front of the completed facility, we felt deep relief. The system was ready. And people were already there.

Safe water exists.

And everything feels different.

Why Off-Grid Matters

The area was recently electrified. However, power outages are frequent and can last two to three days.

Water infrastructure cannot depend on unstable electricity.

That is why we adopted a solar-powered solution.

The system incorporates pass-through technology that does not depend on battery connectivity. Even with only 600–700W of solar input, the system can operate during daytime hours.

Furthermore, many surrounding communities remain unelectrified, and groundwater salinity continues to spread.

From the beginning, we designed the system as fully off-grid. It operates independently of the national grid. Whether in blackout conditions or in unelectrified areas, water does not stop.

For infrastructure tied directly to life, this resilience is essential.

Japanese Technology Supporting the System

The purification core utilizes Japanese hollow fiber membrane technology.

This membrane physically removes turbidity and bacteria such as E. coli—addressing not only visual clarity but also hygiene and safety.

The system also includes an automatic backwash function to reduce clogging and maintain stable performance over long periods. Importantly, it operates without chemical additives.

In regions where maintenance resources are limited, minimizing membrane replacement and chemical dependence is critical.

Technology must not only perform well—it must be sustainable.

Yet, the most memorable aspect of this project was not the technology itself.

It was the smiles of children holding safe water.

No matter how advanced the system, what ultimately matters is that expression.

This Is Only the Beginning

This project covers only one village.

Across Uganda, many communities face similar challenges:

- Villages forced to use contaminated groundwater

- Villages where salinization has rendered groundwater unusable

This is not merely about inconvenience. It affects health, education, and future opportunities.

The era when drilling a borehole alone was sufficient is gradually changing.

A borehole does not always mean safe water.

Water infrastructure is entering a stage where quality matters as much as quantity.

The greatest reason this project succeeded was the presence of a trusted local partner.

We are not delivering technology.

We are sharing it.

We are building it together as a business.

This step has just begun.

And we have no intention of stopping here.